Where should your organization start when addressing fair pay? In this extract from our latest white paper, ‘Cultivating Fair Pay in the Workplace: Your Guide to Global Pay Equity’ we start at the very beginning: the many different terms and lenses we apply to fair pay and how they relate to the laws your business is governed by.

One of the complications when dealing with fair pay issues is that the meaning of ‘fair pay’ is not universally established. We have a number of concepts that all speak to fair pay in different ways, and are more or less relevant to different societies. Some of the more important concepts are pay gaps, equal pay, pay equity, equal pay for work of comparable worth, and/or equal pay for work of equal value.

Learn more about Pay Equity in this digital training video.

(Note that some of these exact terms are used differently in different countries. Our definitions here take a US-centric approach.)

Defining Different Types of Pay Gaps

Pay gaps describe overall differences in pay between classes of people within a grouping, such as a country, sector, or organization. The differences are typically described in terms of differences in average or median pay, but may also be described by other means such as percentile rank differences.

One of the reasons pay gaps are interesting is because they come in two forms:

- Uncorrected

- Corrected

Uncorrected pay gaps are almost always larger because they aren’t taking into account things that may explain the pay gap. Corrected pay gaps are almost always smaller because they represent the gap in pay after various explanatory factors have been accounted for and fed into a statistical model (usually some type of regression).

Explanatory factors may include:

- Economic sector

- Job level

- Experience level

- Company

- Job title or classification

- Tenure

The idea for a corrected pay gap is that you’re looking at the equivalent of the aggregation of differences in average pay between classes of people (such as males vs. females), who have the same characteristics (i.e. “explanatory factors”) in common.

So for example, you would look at the differences in average pay between classes who are in the same sector, the same job type, and have the same range of experience for each combination of sector, job type, and experience range. Then take an average or weighted average of those differences to get a controlled pay gap for the larger group.

Also from the blog: ‘How to Use a Climate Survey to Understand and Nurture Diversity and Inclusion’

Looking Closely at Corrected and Uncorrected Pay Gaps

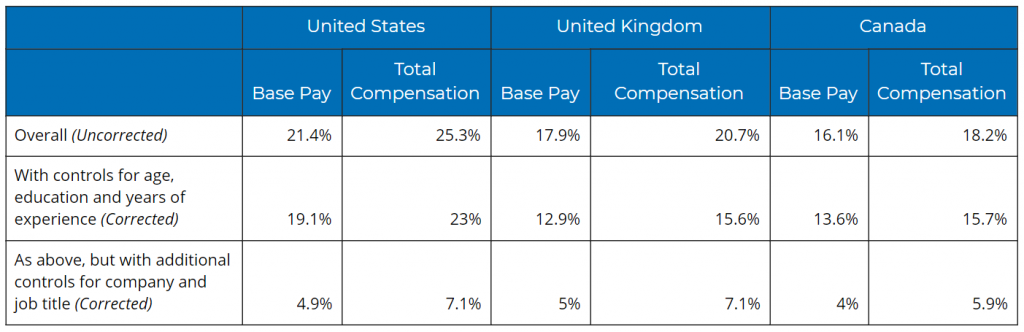

A recent Glassdoor report looked at corrected and uncorrected overall pay gaps in several countries.

Corrected and uncorrected pay gaps between men and women in the United States, United Kingdom and Canada.

In the table above, the addition of ‘corrected’ controls can dramatically close the visible pay gap. However, both ‘corrected’ and ‘uncorrected’ pay gaps implicitly make different assumptions about what is fair, and should be treated with a certain degree of caution as a consequence:

- Attaching meaning to an uncorrected pay gap implies that all factors that create that gap are contributing to an unfair difference in pay. If we say the gap is unfair and most of the gap is caused by differences in sector participation between men and women, then we are effectively saying that the difference in sector participation has some unfair quality to it.

- Attaching meaning to a corrected pay gap implies that the gap is only unfair in situations where classes of people with similar characteristics still have differences in pay.

These differences in interpretations between pay gap types illustrate the reason for different ethical and regulatory approaches to fair pay, and lead us into the other important fair pay concepts mentioned earlier.

Pay Equity Versus Pay Equality

Pay equity means providing equal compensation for employees who are similar in terms of job duties and important characteristics such as experience, tenure, location, and job performance.

Pay equity is in line with looking at controlled pay gaps. In the United States, fairness in pay is usually considered through the pay equity lens, and is captured in the Equal Pay Act. However, government contractors must abide by regulations that indirectly address pay equality through various affirmative action programs.

Pay equality is a broader concept than pay equity and refers not just to equal pay for people in similar situations, but also to the equality of opportunity, motivating factors, and acceptance that lead to the proportional holding of positions across the pay spectrum.

Pay equality is in line with looking at uncontrolled pay gaps and is more relevant in countries outside of the US. For example:

- France has laws that may hold companies accountable for gender differences in promotion rates and top earner representation, as well as for gender differences in pay and pay increases.

- The UK requires larger companies to disclose uncontrolled pay gaps between all male and female employees, along with the percentage of women in each pay quartile.

More on Pay Equity: ‘Beyond the Headlines – How a Pay Equity Strategy Translates to a Competitive Advantage’

Continue Reading

Continuing the discussion in the full version of this chapter, our authors look at other equal pay terminology. Terms such as “equal pay for work of equal value” and “equal pay for work of comparable worth” are put under the microscope, going on to consider how these principles relate to fair pay laws in the US and Europe.

Deeper into the white paper, we also cover:

- The mechanisms of unfair pay, including the myths and biases that undermine the compensation of certain groups

- The increasingly compelling case for why your organization needs to care about, and take action on, pay inequity

- A five-step plan of action for organizations that want to create fairer pay practices

Download your copy of the white paper today.

Inspired to tackle the issue of fair pay and pay equity in your organization immediately? Contact our team for more information.

About the Author

About the Author

Patrick McNiel, PhD, is a principal business consultant for Affirmity. Dr. McNiel advises clients on issues related to workforce measurement and statistical analysis, diversity and inclusion, OFCCP and EEOC compliance, and pay equity. Dr. McNiel has over ten years of experience as a generalist in the field of Industrial and Organizational Psychology and has focused on employee selection and assessment for most of his career. He received his PhD in I-O Psychology from the Georgia Institute of Technology.