What causes gender-based pay inequality? While there are a large number of contributing factors, the list can be narrowed down to four principal causes that organizations, governments, and individuals must be aware of and prepared to counteract. In this article, we take a look at these causes and what they mean for your approach to diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Fundamental Cause #1: Bias

The first area of note is psychological and social bias. This is really a lot more than just simple prejudice—though sometimes that’s the form it takes. Most commonly, it’s really a systematic error in how we think, and sometimes such errors can be to the detriment of entire groups of people. There are countless ways that bias can affect pay differences between men and women, but there are three areas where gender biases play particularly significant roles.

i) Starting Pay

In countries like the U.S., starting pay is positively affected by negotiations. There’s a long history of studies suggesting that women are less likely to negotiate pay, or less likely to negotiate when not told that wages are negotiable, or more likely to anticipate a backlash when negotiating. Even when some modern surveys have suggested women may actually now be negotiating more than men, they still earn less. Starting pay is also affected by prior pay, which tends to be lower for women.

ii) Performance

Just as psychological biases alter the value signals that indicate how much a person is worth to the organization during starting pay negotiation, these same biases affect every subsequent opportunity, including:

- Performance metrics

- Promotion chances

- Promotion and merit pay increases

- Bonus distributions

iii) Leadership Likelihood

In many countries, women are less likely to be viewed as leaders or as having leadership qualities. This is its own form of bias, which stems in part from an association between leadership and masculine qualities. But it also comes from the lack of prominent models for what female leadership looks like, and from traditions that cast women in non-leadership roles. All these factors decrease the likelihood that women will become prominent in their field, promoted in their organization, or chosen for higher-level positions in their organization.

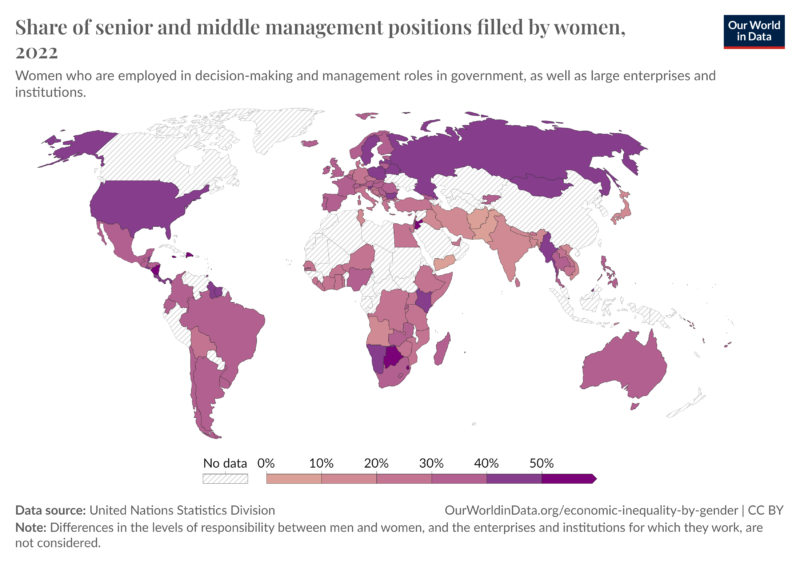

Given that women make up more than 50% of those populations, we would generally expect women in approximately 50% of leadership roles. The degree to which we don’t see that. can be pretty striking.

Source: OurWorldinData.org

The map above, based on UN Statistics Division data, provides the worldwide gender distribution in senior and middle management positions. Globally, that distribution is largely in the 30-40%, with the U.S. actually being one of the few nations in the 40-50% range (where it has been since 2017). However, this trend of female non-participation only becomes more extreme as you go up the ladder, with only 5.6% of Fortune Global 500 companies being run by female CEOs.

ESSENTIAL PAY EQUITY INFORMATION | ‘Your Guide to State-Level Pay Transparency Laws (As of September 2024)’

Fundamental Cause #2: Culture

The second fundamental cause of pay gaps is culture. In many countries, women are steered away from higher-paying fields. Sometimes this is done in an overt manner by cultural norms and certain practices in a field that can be actively hostile towards women.

However, this is often done more subtly via the kinds of messages that young girls and women get from advertisements, cultural depictions, role models, and other societal signals. This messaging implies that it’s good for women to be in certain professions, but less desirable for them to be in others—which often also happen to be higher-paid professions.

Furthermore, the work done in fields that are dominated by women tends to be undervalued to the extent that when women take over male-dominated fields, pay drops. This is a consistently well-documented phenomenon that seems to have very little to do with required education levels or the effort, working conditions, or responsibility levels involved.

WHY DEI? | ‘4 Reasons to Invest in Optimizing Your Affirmative Action and DE&I Programs’

Fundamental Cause #3: Family Life

The third fundamental cause of pay gaps, and one perhaps central to the cultural reasons women tend to make less money than men, is that women sometimes have children.

The immediate reason the ability to have children negatively affects pay is that many companies (and the people in them) have historically been resistant to taking on part of the burden associated with child-rearing. This attitude persists to some degree to this day. Whether through maternity leave, flexible hours, lower employee availability, additional insurance coverage, or the perceived additional risk that a woman will leave for family reasons, employers and supervisors tend to weigh issues related to having children against women.

Furthermore, women do not seem to get credit for what having children demands of them. Time spent staying out of the workplace is unfairly viewed as a void of work experience, yet raising children and taking care of family is a formative experience that brings incalculable value to a person and their ability to deal with people and situations that are transferable to the workplace. Much like going to college, it’s a set of experiences that helps round a person out and makes them generally more capable, responsible, and ready for leadership roles.

Fundamental Cause #4: Real Differences in Tendencies Between Genders

Finally, there are a number of actual differences between men and women on traits that have some effect on pay within the cultural contexts mentioned above. To be clear, these are not black-and-white qualitative differences between men and women, but different trait-level tendencies in the populations of men and women. When these trait spectrums are plotted on a graph, there’s a large amount of overlap between men and women but men will be more concentrated on one end of the spectrum and women on the other.

For example, more men may score lower on a trait such as agreeableness, and more women may score higher. There may be men who score high on this trait, but when viewed as a population, there are fewer men than women with such a score.

Culture tends to create and magnify, gender differences (note that it can suppress them as well, but this is rarer). This creates feedback loops that reinforce and exacerbate gender differences. So when we measure consistent differences between men and women in diverse populations on various characteristics and traits, it’s essentially impossible to know to what degree those differences are due to biological difference, and which are due to cultural influence.

There are dozens, if not hundreds of characteristics that have been studied and that show gender differences. However, many of these are only or almost entirely due to cultural influences, and most of them have no apparent relationship to how people get paid. Nonetheless, there are a few trait differences that seem to be universal across cultures. They show up early in development before culture can have large effects and relate to how much money a person might earn. These include:

i) Risk Assessment and Tolerance

Women tend to be better at recognizing risks and dangers of all kinds. Once a risk has been identified, women are more likely to try to reduce the risk or to avoid the risky situation. In combination, these traits may cause women to disproportionately under-engage in things like entrepreneurship, which is highly risky and associated with higher pay. This applies to both internal and external entrepreneurship (i.e. both inside and outside an existing company).

Low risk-taking behaviors may also reduce opportunistic behaviors. When uncertainty is involved, it could also lead to lower social risk-taking, which is involved in the kinds of dominance games and credit-taking that often lead to leadership positions and roles.

ii) Agreeableness

Women tend to be more agreeable, and agreeableness tends to be negatively correlated with position in an organization. Agreeable people are more likely to follow others rather than establish themselves as leaders. They’re more likely to share or give credit to others, even if it wasn’t earned. They’re more likely to stay in situations that aren’t ideal for them, rather than breaking from that group and moving on. It should be noted that the effects of agreeableness on promotion probability seem to be moderated by context. It has greater negative effects in highly structured environments (think civil service), but may have a more positive relationship with higher levels in more collaborative and flat organizations.

iii) Interest in People Versus Things

Women also tend to be more concerned with people and less concerned with objects and things as compared to men, and this tendency has led to differences in participation in science and technology fields, which generally have jobs that are compensated at a higher rate.

iv) Preference for Meaningful Work

Finally, a Columbia Business School study showed that women tend to be drawn more to work that is meaningful and seen as contributing to the wellbeing of others. Unless there are extreme barriers to entry (such as becoming a medical doctor) this type of work tends to be compensated at a lower rate, in part as a consequence of more people being drawn to it. Conversely, men are more likely to do explicitly non-meaningful work, which attracts fewer workers and results in higher pay.

The study quantified male and female interest in different types of work, the “meaning” of that work, and the effects of pay differences on occupational interest. It concluded that choosing meaningful work might account for as much as 9.5% of the uncorrected pay gap.

LEARN ABOUT FEDERAL CONTRACTOR PAY EQUITY REPORTING | ‘Pay Equity Reporting FAQs: Answers to 10 of Your Questions After OFCCP Scheduling Letter Updates’

In Conclusion

By understanding these root causes of gender pay inequality, we can begin to build a framework for addressing them. This framework involves a number of different measures, such as prohibitions, incentives, goals, and requirements, as well as parental and career support. Pay equity self-auditing and planning are also critical elements of your approach. Pay inequality can seem like a large, complex, and hard-to-tackle issue, but Affirmity can help. We’re here to identify equity issues in your business and shape your response.

To talk to an expert about how we can support your pay equity efforts, please contact us today.

About the Author

Patrick McNiel, PhD, is a principal business consultant for Affirmity. Dr. McNiel advises clients on issues related to workforce measurement and statistical analysis, diversity and inclusion, OFCCP and EEOC compliance, and pay equity. Dr. McNiel has over ten years of experience as a generalist in the field of Industrial and Organizational Psychology and has focused on employee selection and assessment for most of his career. He received his PhD in I-O Psychology from the Georgia Institute of Technology. Connect with him on LinkedIn.

Patrick McNiel, PhD, is a principal business consultant for Affirmity. Dr. McNiel advises clients on issues related to workforce measurement and statistical analysis, diversity and inclusion, OFCCP and EEOC compliance, and pay equity. Dr. McNiel has over ten years of experience as a generalist in the field of Industrial and Organizational Psychology and has focused on employee selection and assessment for most of his career. He received his PhD in I-O Psychology from the Georgia Institute of Technology. Connect with him on LinkedIn.