In response to the economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, organizations are being forced to assess their current situations, simulate future scenarios, and make difficult and painful decisions. As a result, reductions in force (RIFs), layoffs, and furloughs are being considered or enacted by many employers.

Such actions are difficult on many levels and require extreme care and forethought. Organizations that downsize must do so in a way that avoids discrimination and bias, and conforms to legal requirements. In this article we discuss some of the most effective things an organization can do to avoid bias and adverse impact when downsizing its workforce.

What to Do Before You Downsize

But first, an organization may wish to consider alternatives to downsizing actions, which can have highly negative short- and long-term effects on market position, strategic advantage, basic capabilities, culture, employee perceptions, and public perceptions. Downsizing also erodes trust and motivation in remaining employees and causes existential anxiety. Alternatives such as pay or hour reductions, payments in stock, or deferred payments can solve short- or long-term financial issues with a much lighter non-financial impact on the company, employees, and future capabilities. Such actions, if delivered properly, are also less likely to create adversarial conditions with employees and are less likely to instigate litigation. Additionally, such actions can sidestep issues of bias and discrimination if they are applied in a uniform manner.

If downsizing is necessary, whether from a RIF, layoff, or furlough, each downsizing action represents one or more employment decisions. And, these decisions are subject to equal employment opportunity laws. The most commonly relevant of these laws are:

- Civil Rights Act of 1964 and 1991

- Age Discrimination in Employment Act

- Americans with Disabilities Act

- Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act

- Executive Order 11246 (applies to federal contractors)

- Section 503 of the Rehabilitation Act (applies to federal contractors)

- Vietnam Era Veterans Readjustment Assistance Act (applies to federal contractors)

- Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures (UGESP – not a law, but given a similar weight in court proceedings)

- Also check state and local laws

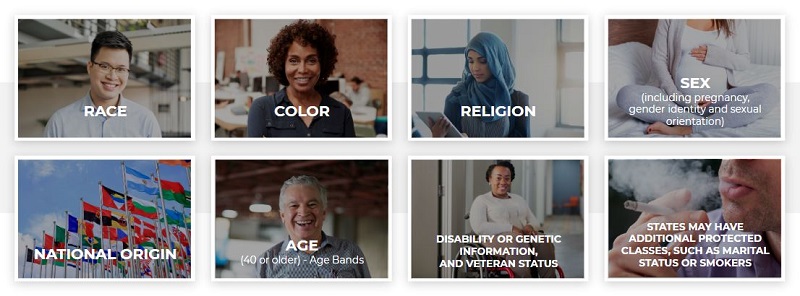

Collectively, these laws prohibit discrimination based on race, ethnicity, sex (including pregnancy, gender identity, and sexual orientation), age (40 or over), disability, religion, national origin, genetic information, and, veteran status.

A Diverse Team to Make Unbiased Decisions

To avoid adverse impact against a protected class defined by these laws and to minimize bias, it’s best to develop and consistently apply criteria for selecting who will leave when a downsizing action occurs to employees in pools being considered for downsizing. These criteria should reflect business necessity and fulfill some legitimate business purpose. They should take future needs into account. And, they should be based on information that would not reasonably be expected to disfavor a protected class.

It’s also recommended that criteria be developed by a diverse team. Such a team will increase the likelihood of actual and perceived fairness, and help to ensure that criteria are unbiased.

An example of a biased criterion that organizations are often tempted to use is level of pay. Given the typical goal of most layoffs, which is a better financial situation, level of pay seems to make good sense. However, level of pay is typically associated with age, which defines a protected class. This makes use of pay level tricky to justify as a criterion for selection during downsizing.

Criteria used for downsizing can be simple or complex. A simple criterion would be something like the ‘last in, first out’ rule. This is where people are ordered by tenure and cut from smallest to greatest tenure until the number of cuts needed are made. A more complex set of criteria might involve some combination of performance reviews, tenure, critical skills, productivity, etc, which are treated equally or weighted in some manner. This would result in a single score that can be used to compare employees.

Objective vs Subjective Criteria for Employee Evaluations

Whether part of a simple or complex scheme, each criterion used to compare employees can be placed on a continuum from completely objective to completely subjective.

Objective criteria are not open for interpretation. Tenure, number of disciplinary actions, and average profit margin on sales are examples of more objective criteria. These are simply numbers that come from well-defined conditions. Subjective criteria, however, are open to interpretation. Examples of subjective criteria include overall performance reviews by supervisors, 360 feedback scores, ability to present and communicate, and safety orientation. They all require judgment to determine a level or score on the criteria, and are judged from a different perspective by each individual judge.

Then there are criteria that are somewhere between objective and subjective, such as customer satisfaction metrics. Customer ratings are themselves subjective, however these ratings are also important business metrics that are often treated as objective.

As a general rule, it’s better to use criteria that are closer to being objective. They are typically less influenced by the cognitive biases associated with discriminatory behavior, and they tend to be more clearly defined. Even so, subjective criteria may still be needed to retain the most effective workforce after downsizing. In such cases, the best practice is to make subjective criteria as objective as possible. This can be done by:

- defining criteria clearly,

- basing criteria on observable behavior or metrics as much as possible,

- and creating well crafted tools that allow those who must make judgments to accurately place employees at different levels of a criterion.

For example, if customer service orientation is of paramount importance, then instead of simply asking a supervisor to place an employee on a scale from 1 to 5 on customer service orientation, the levels of the criterion may instead be defined by a combination of customer rating scores, customer complaints, quality and frequency of specific observable customer oriented behaviors as judged by the supervisor (who has been well trained for this task), and knowledge of what to do in various difficult customer-facing situations. The assessment of customer service orientation is still subjective, but to a lesser degree.

Avoiding Bias

When downsizing, good criteria may be all that’s needed to avoid bias and adverse impact against a protected class, but it’s still a best practice to check that this is the case. Before actually implementing a downsizing action, it’s important to see what such an action would do to various protected classes. At a minimum, a series of impact ratio analyses should be calculated to see if employees of a particular gender, race, or age category (40 or over) are disproportionately selected for downsizing.

Additionally, depending on the prevalence of classes in the pool of employees being considered, it may be desirable to calculate additional impact ratio analyses for other protected classes such as veterans and people with a disability. It’s also important to calculate a statistical test, such as a Fisher’ exact test, for each impact ratio analysis to help determine if disparities are meaningful.

What Is an Impact Ratio Analysis?

An impact ratio analysis compares the selection rates of two groups, such as males and females, and shows the relative rate of selection for one group compared to another.

For example, if we have 500 females and 500 males in a group of employees and 100 females and 50 males are selected to leave the organization, then the selection rate for females is 20% and the selection rate for males is 10%. The relative rate, or impact ratio, is then calculated as the lowest rate (that is, the rate of the favored group in a downsizing situation), divided by the highest rate. In this case the impact ratio is 10/20 = 50%.

So, men are selected to leave at only half the rate of women. Guidelines from UGESP specify that since this is below an 80% threshold, the impact ratio of 50% is an initial indicator of adverse impact. A statistical test will also let you know if the differences in selection rates are likely to occur from chance. If chance is an extremely unlikely explanation for these differences, then this is further evidence of adverse impact.

Should You Consider Pausing Downsizing?

If adverse impact is evident when utilizing the chosen criterion or set of criteria, it’s highly recommended that the downsizing process be paused to review the parameters of selection.

Examine each criteria to see which is contributing to adverse impact by calculating group differences in average score levels, impact ratios, and appropriate statistical tests of group differences to see if one or more criteria out of the full set of criteria are causing the overall adverse impact in selections for downsizing.

Consider how well the criteria causing adverse impact fulfill the organization’s needs, and how defensible using them would be. Also consider alternative criteria that might fulfil the same purpose without causing adverse impact. If use of a criterion can’t be justified or if a better criterion is available, then replace or eliminate the adverse impact causing criterion and rerun the impact ratio analyses and statistics for the overall process.

Keep looking at adverse impact statistics for the overall process and individual criteria until adverse impact is not evident or all criteria are determined to be needed and defensible.

Do you need help with avoiding bias and discrimination? Check out our talent management decision analysis resources, or contact Affirmity for expert advice today.

About the Author

About the Author

Patrick McNiel, PhD, is a principal business consultant for Affirmity. Dr. McNiel advises clients on issues related to workforce measurement and statistical analysis, diversity and inclusion, OFCCP and EEOC compliance, and pay equity. Dr. McNiel has over ten years of experience as a generalist in the field of Industrial and Organizational Psychology and has focused on employee selection and assessment for most of his career. He received his PhD in I-O Psychology from the Georgia Institute of Technology.